SELECTED

Exhibitions

CAMERA OBSCURA

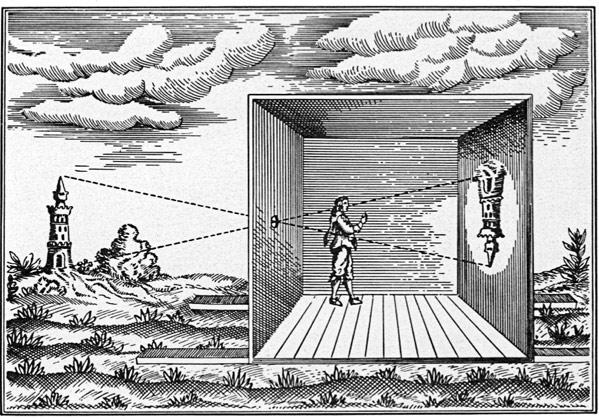

Camera obscura is Latin for dark room. Camera meaning room and obscura meaning dark.

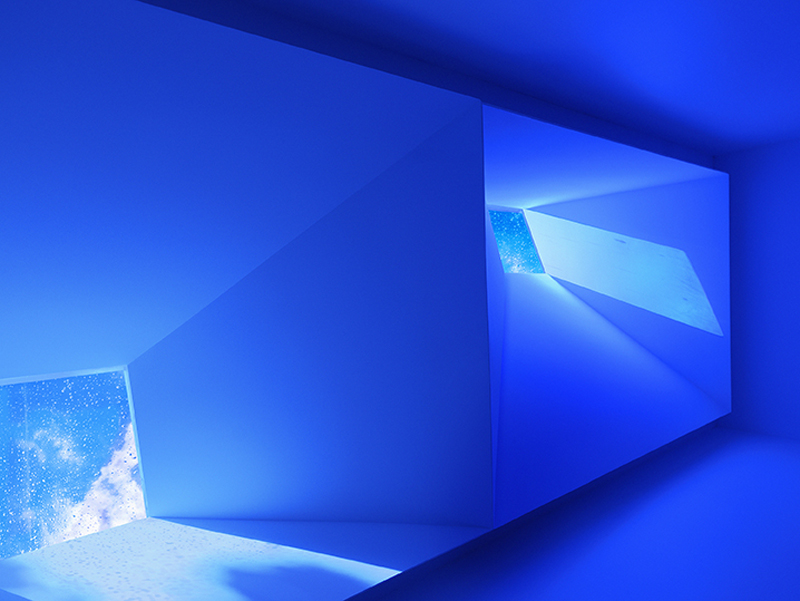

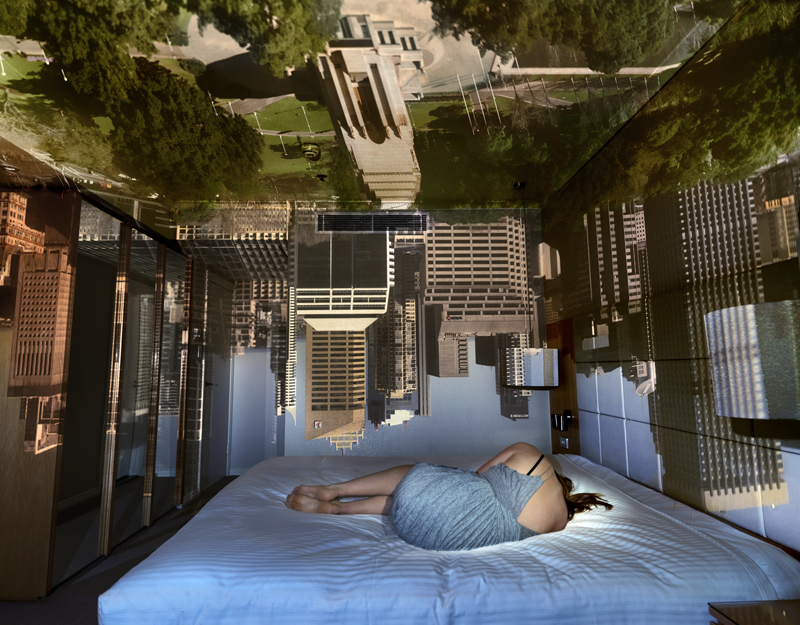

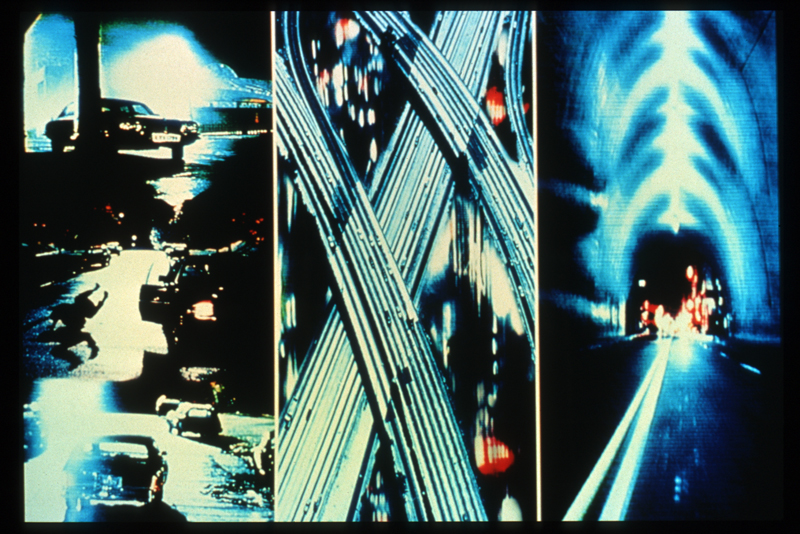

The images in Dark Wonder (2016), Ray of Light (2016), Cloud Land (2015),Guest Relations (2013-2014) are camera obscura images. The camera obscura is created by blacking out a room and making a small aperture to the outside world. This is the only light source in the room and the external view is projected (via the opening) onto the walls, ceiling and floor of the room. The outside world literally wallpapers all the surfaces of the room. I am in the room with a camera and photograph the room with the exterior view projected over the interior of the room. Because light travels in a straight line, everything appears upside down and in reverse. The ground is projected onto the ceiling and the sky appears on the bed or floor of a room. Buildings hang from the roof upside down and cars drive across the roof and down the walls.

There is no digital manipulation. Everything you see in the image is happening in real time and each room is a unique experience. The upside down, reversed view of the world is actually the way that images form on the back of the retina. As we have evolved to walk upright it is our brain that flips and reverses the image for us. Otherwise it would be too difficult for us to navigate our way around the world.

To accompany the Ray of Light series in the 2016 Adelaide Biennial I made two live camera obscuras to allow people to spend time in the darkened room and experience the movie like quality of the projection of the outside world. Subsequently I have made a number of these ‘live’ rooms, to accompany exhibitions, as the experience of being in the room is quite compelling. The collision of the exterior world with the interiors of the rooms, the overlay of real and projection creates a temporary liminal space; you see all the movement that is taking place, clouds moving across the sky, people, cars, boats, planes etc. moving in and out of the scene. All playing out before the audience in the room, the experience is one of being in the world but removed from it at the same time. Transience characterises the camera obscura, as each room is only alive for a few hours, depending as it does on the position of the sun in relation to the room.

Brief History

Many societies claim the invention of the camera obscura. There are records citing evidence of the camera obscura in China in 390 BC by a philosopher named Mozi and other historians date the camera obscura from Alhazen, a Persian philosopher, who utilised it to develop a state of the art theory of the refraction of light. In Europe, Euclid’s Optics (c. 300 BC) mentioned the camera obscura as a demonstration that light travels in straight lines.

During the Renaissance, the pinhole camera obscura was equipped with lenses and mirrors and transformed into the optical camera obscura of the early modern period. The hey-day of the optical camera obscura was between 1600-1800 and it sits alongside the microscope and the telescope in terms of its impact, ushering in a new approach to optics, opening up new views of the visible world and shaping a new understanding of vision itself. In 1589 Giambattista della Porta celebrated the wonder of seeing an image separate itself from its object for the first time, and the uncanny effect of the inversion of the image as it was projected into the room.

Its employment for painting, which one can reasonably assume but not prove, is attributed to both Vermeer and Caravaggio. While its use in the 17th century is difficult to prove it is well documented for the subsequent 18th century. The Venetian cityscapes (veduta) of Canaletto (1722-1780), may be the most famous paintings produced with the aid of a camera obscura.

Despite the camera obscura being adopted as an instrument of rational sight in the 18th century, the problem of our vision’s simultaneous enmeshment in and removal from the world, which the camera obscura spectacularly exemplified, wouldn’t go away. What worried philosophers and scientists such as Descartes, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton was the question whether vision was just inert vitreous optics screening pictures in front of our brains, or was the human spirit, or soul necessary as well, to tie us into the world we subjectively experience? Where was our faculty of perception located, just behind our eyes, or somewhere else in our spirit? Where did we end and our world begin?

Leonardo da Vinci and Rousseau argued that the representation of the external world inside the camera obscura supports the view that the pictures in the blank screen of the mind accurately represent ‘objective reality’ (representation). Conversely Marx, Nietzsche and Freud saw the images shining on the mental screen of the mind’s inner chamber as delusory inversions of social relations and conscious knowledge, whose origin has been forgotten.

While Marx was using the camera obscura as a handy metaphor in his revolutionary thought, actual camera obscuras were being enjoyed by the proletariat. In Australia they were becoming popular attractions, rather than scientific instruments. From the 1850s camera obscuras, probably built into carts, were being advertised as feature attractions in Australian travelling fairs and exhibitions and intrepid entrepreneurs began to build permanent camera obscuras, out of either stone or wood, at prominent vantage points in Manly, Wollongong, Brisbane and Adelaide.

STILL LIFE

Characterised by meticulous realism, dynamic compositions, powerful forms and evocative lighting, still life is one of the most enduring and significant genres in Western art. Still life captivates us with close-up views of objects no longer living but far from lifeless. Every pictorial element conveys some social or moral content or serves as a reminder of the transient nature of life.

The still life genre provided me with a working methodology to investigate and re-present Enlightenment collections dating from the seventeenth to nineteenth century in Europe and Australia. The exhibitions Tall Tales and True (2011), Empire Line (2009), The Great and the Good (2008), Beau Monde (2005) and The Collector’s Nature (2003); are diverse in their range; from natural history collections housed in the National herbarium of the Netherlands to artefacts sourced from Palladian villas and Neo-Gothic estates held in the property portfolios of Sydney Living museums.

museums order and isolate collection material based on provenance, maker, and materiality. Rather than showcasing items in their traditional museum display I employed the Dutch, Spanish and American still-life traditions to re-interpret these collections, giving the viewer a more intimate reading of the objects by creating compositions that allude to the world that gave rise to them. The images, 9pm Elizabeth Bay House, The Duke of Northumberland’s Tablecloth, and The Butler’s Tray, all create the impression that the settings have just been left momentarily.

More than stunning compositions, the emblematic codes of the still life genre pose recurring philosophical questions about beauty, truth, and wisdom, Miss Eliza Wentworth’s Glassware as well as being a particular set of glassware also references the fragility and precariousness of life. In the still-life tradition, glass, particularly shattered or broken glass, refers to the frailty of life, but the still-life composition also served to demonstrate that by preserving the object permanence can be lent to the most fragile. Table of Industry, based on the book still life tradition, is a reminder that even knowledge is transient, and continually changing.

The still-life qualities of rendering detail lovingly and creating a powerful mise-en-scene through lighting lend themselves brilliantly to photographic interpretation. The sharpness of the lens, and the control over lighting allows the photographer to reveal detail and invest both simple and intricate compositions with a heightened reality.

Underpinning the compositions, whether simple (The First Cut, Walnuts, Salmon) or complex (Fontaine de Vaucluse, Mr. Macleays Fruit and Flora, Rouse and the Cumberland Plain, Saison 93-94), is the search for order and meaning. Every element is there to educate and elucidate, and the image is incomplete unless the viewer participates in this de-coding, inviting an investment in the image by both the maker and the viewer.