Robyn Stacey | Nothing to see here

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

If this video does not start automatically, roll mouse over image and click arrow to start. enquire about this work

If this video does not start automatically, roll mouse over image and click arrow to start. enquire about this work

Nothing to see here

In his book Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder describes an art contest between fifth century artists Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Zeuxis’s painting of grapes appeared so real that, upon its unveiling, birds attempted to eat them. Next it was Parrhasius’s turn, and he asked his rival to pull aside the curtain concealing his work. When Zeuxis tried, he discovered the curtain itself was a painted trompe l’oeil. “I have deceived the birds, but Parrhasius has deceived Zeuxis,” declared the defeated artist.

Thus begins the curtain’s long and storied role in cultural history. For photographic artist Robyn Stacey, the curtain is a device designed to impart neutrality, yet nonetheless hangs heavy with resonance. This makes it the ideal subject for a pure exploration of light and colour while opening up possibilities beyond the visual. For her first exhibition with Darren Knight Gallery, Nothing to see here, Stacey has created three series of work with the curtain as their nexus.

As is alluded to in Pliny’s tale, the curtain was used in the past to cover paintings, not only for dramatic unveilings, but also for protection from the elements. Once opened, it would create a proscenium arch around its painted charge. This miniature scene is writ large in the theatrical arts, where the curtain is drawn back prior to the commencement of a performance or film.

Stacey’s suite of black-and-white photographs featuring portraits considers the cinematic aspect of this lineage. Created by projecting Super8 film onto a custom-made curtain, the resulting images explore the gaze between viewer and subject, and the luminescent attraction of early screen stars. Some of these characters are taken from B-grade 20th century European cinema, their relative anonymity enhanced through the effect of the projection. Moving close to these nearly human-scaled photographs one sees only light and shade, while stepping back from them reveals their ghostly subjects. These actors float, neither behind nor in front of the curtain, which is cast in a role Stacey has termed “a membrane between reality and allegory.” In The man who would be king, actor Terence Stamp (known in the 1960s as the world’s best-looking man) is depicted in a still from a 1980s film. His face looms through the curtain, downcast eyes ringed with shadow and dark facial hair conjuring any number of mysterious characterisations.

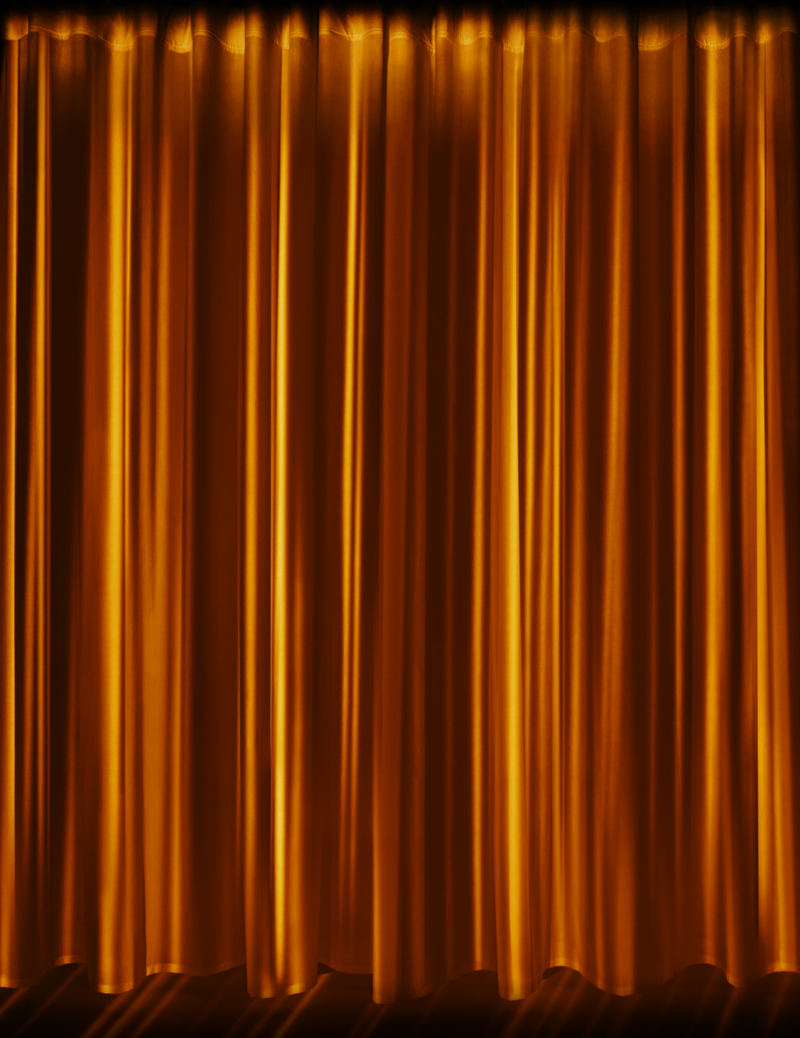

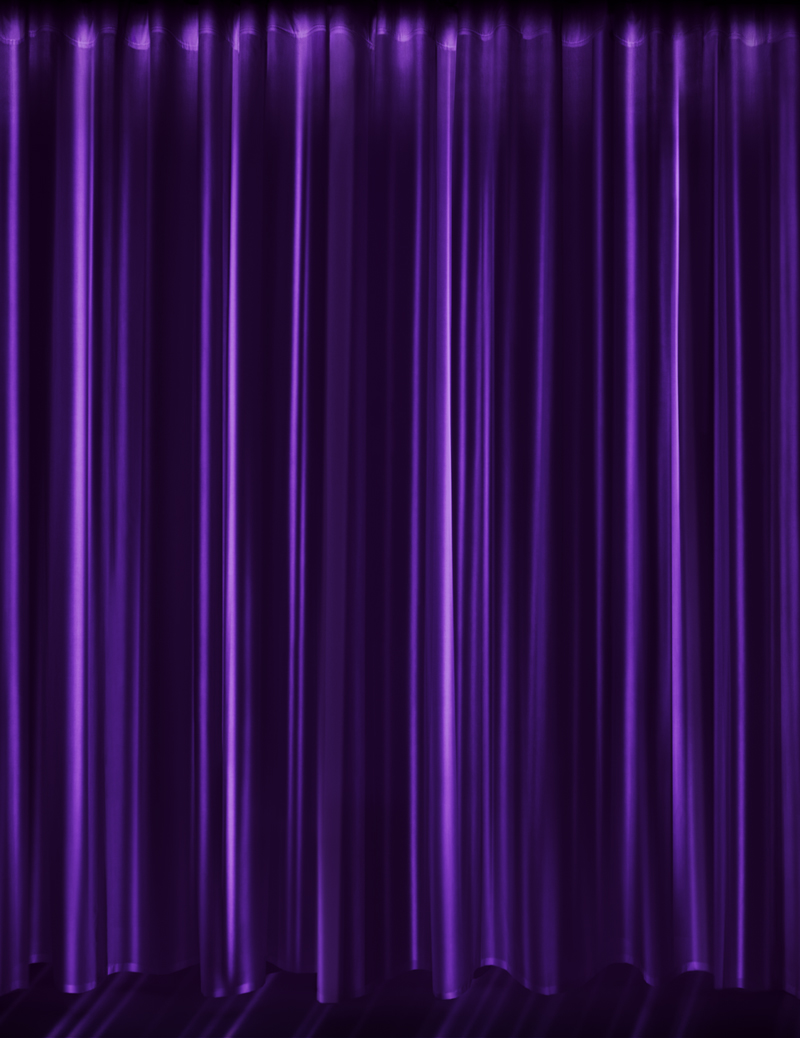

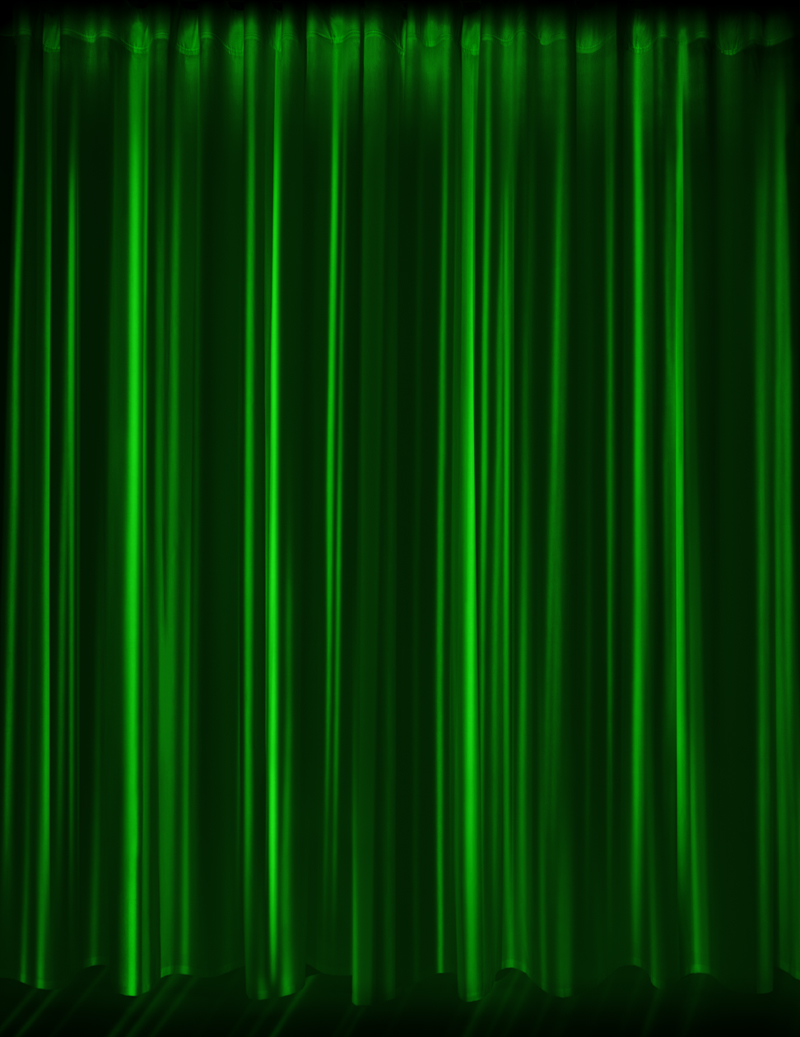

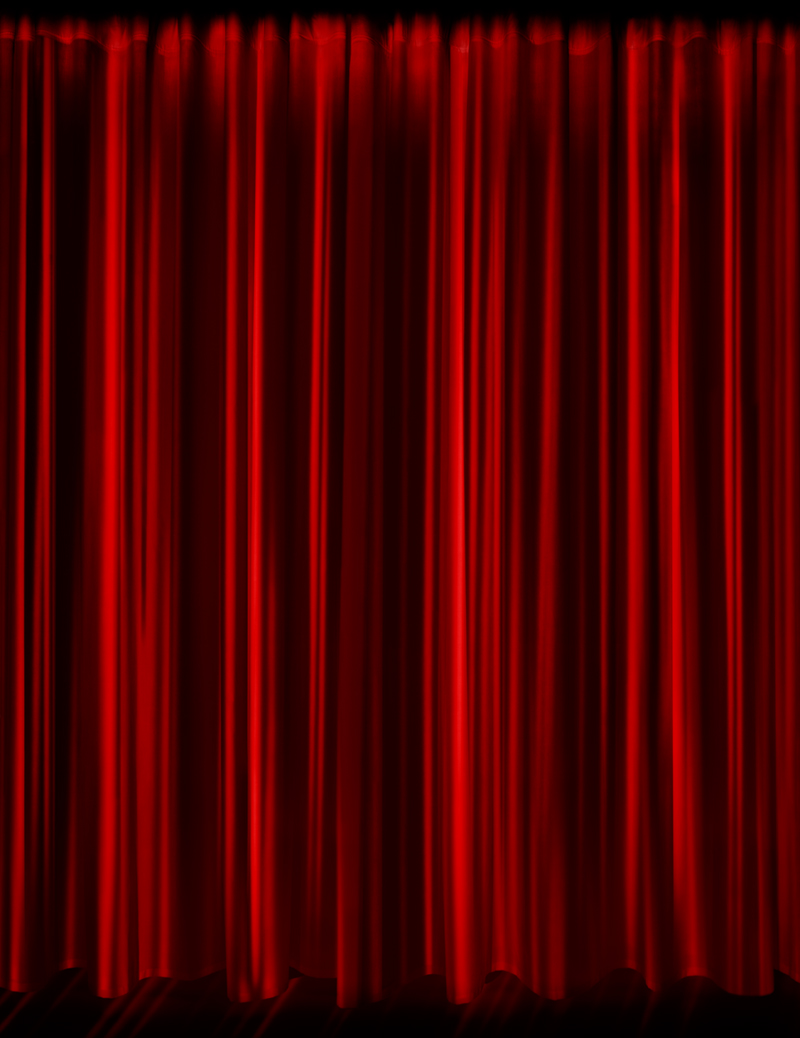

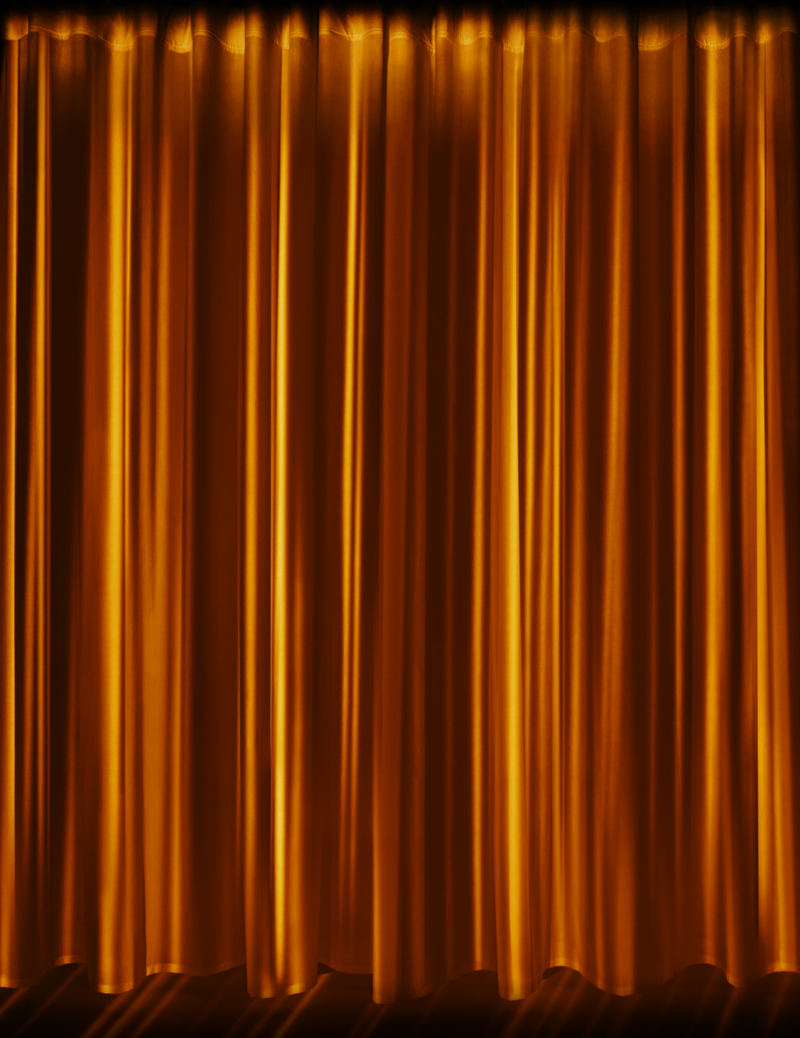

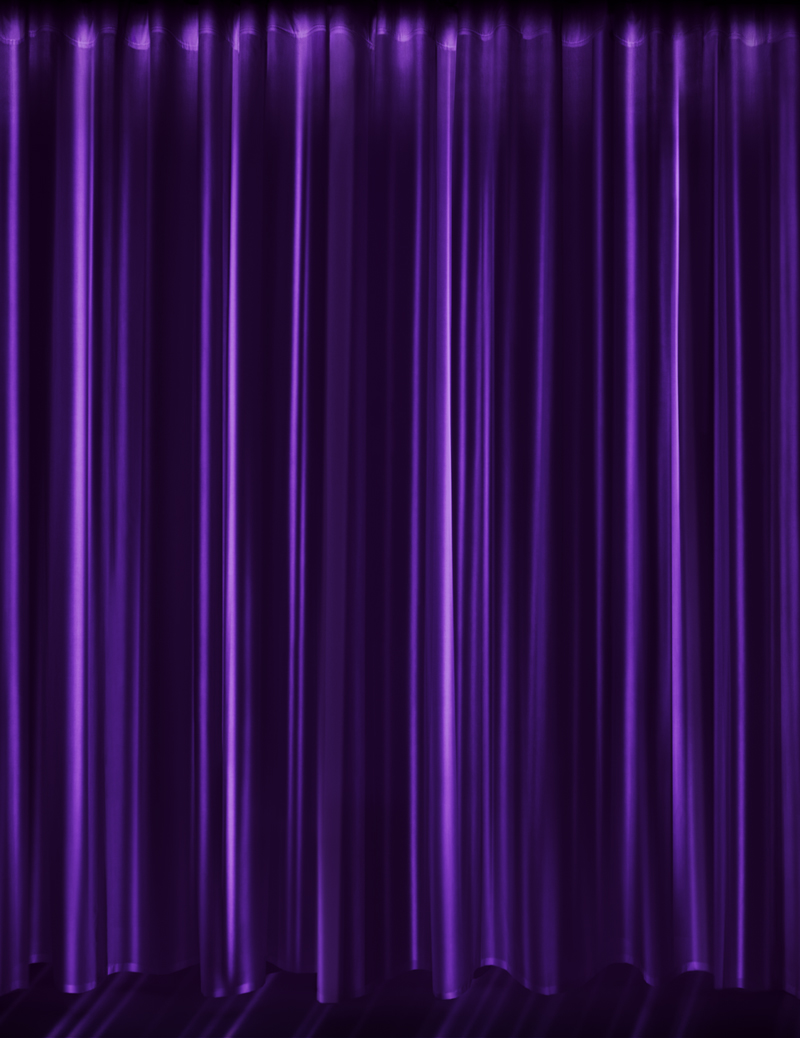

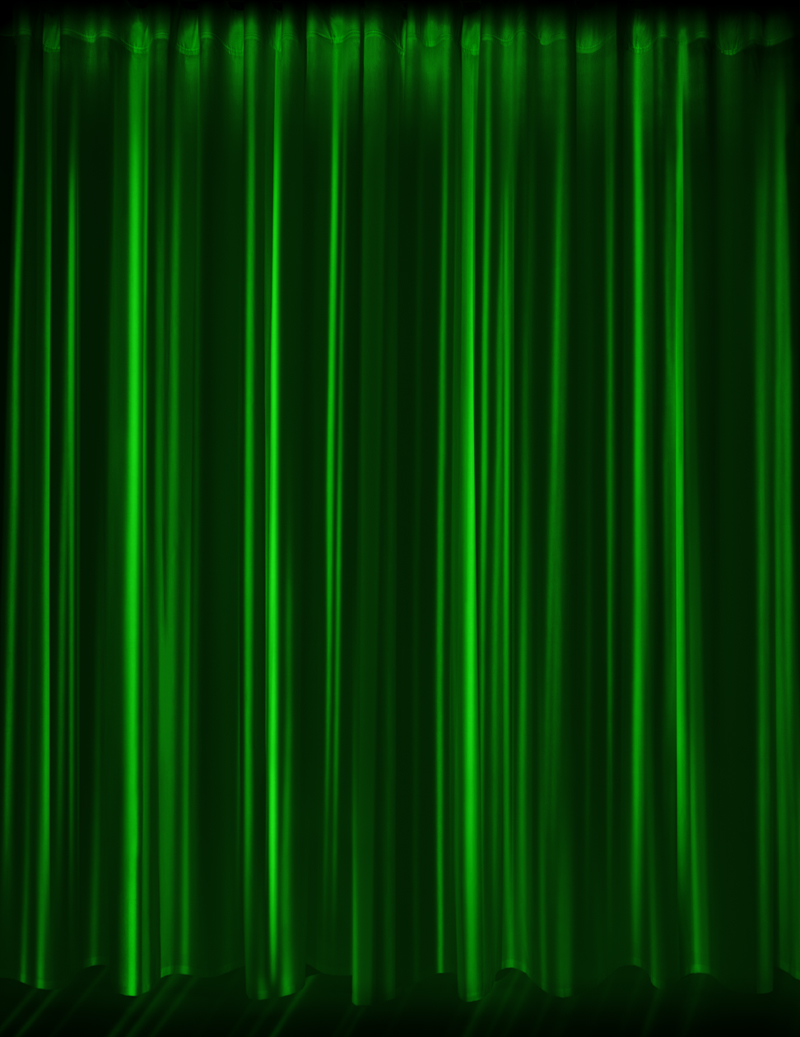

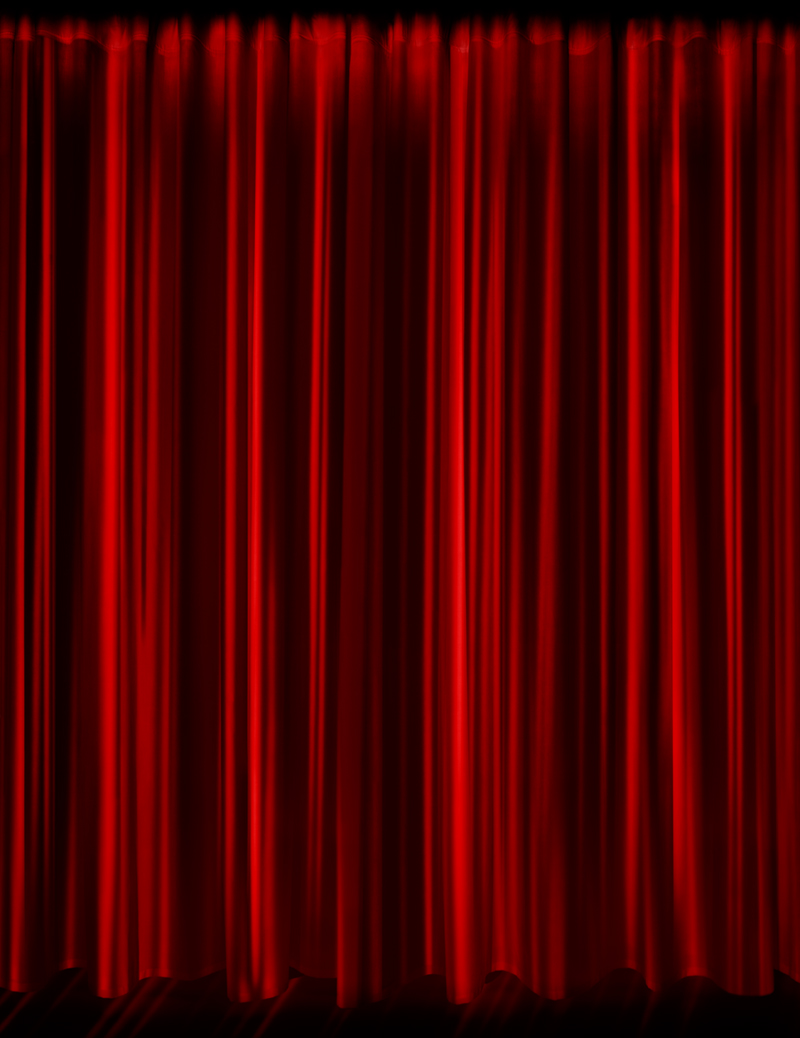

For artists throughout history, drapery has proven a handy device in the construction of still life composition, while the rendering of vast swathes of textile in paint or stone has provided ample opportunity for near-abstract aesthetic exploration. In the suite of coloured works Stacey has made for Nothing to see here, the curtain becomes the background and foreground, subject and object. Stacey constructed these images by projecting an image of a curtain from a scene in the 1941 Orson Welles film Citizen Kane onto the curtain in her studio. Coloured gels placed over the camera lens allow for pure exploration of colour as well as light and shade.

The colours in this suite of works were chosen for their photographic connections, ancient and modern respectively. The colours red, green and blue form the basis of colour photographic film, while gold and purple have alchemical and philosophical evocations. Unlike the suite of black-and-white images, these works have no human subjects, they are neither portrait nor landscape. However by laying bare the object of concealment, Stacey is able to create richly detailed studies of colour and light. One’s eyes trace the folds of the fabric, the tonal differences seeming also to describe changes in temperature and volume.

The term ‘photography’ comes from photos, the Greek word for light, and the inextricable connection between light and time is explored in the final works in Nothing to see here, a series of lenticular prints. These works are constructed of numerous layered images which combine to produce still, yet dynamic works. As the viewer moves before the photograph, the image shifts: through a curtain which changes from golden to grey, or a face hovering in and out of the drapery. Here, Stacey has captured a temporal, as well as physical, fluidity.

The act of ‘drawing a curtain’ can be one of either revelation or concealment. The complete etymology of the word ‘photography’ is ‘drawing with light’, and in this case the curtain acts as an extension of this notion of light as a tool, illuminating the truth and masking it. There is a familiarity and intimacy to this soft apparatus, yet a sense of grandness and authority too. Throughout Nothing to see here, the curtain is identifiable as such, its seams and hems visible at the top and bottom of the composition. The space beneath the curtain and floor “lets interpretation in” as Stacey has put it, serving as a reminder of the possibilities of this theatrically suspenseful yet poker-faced device.

Chloé Wolifson

September 2019

Robyn Stacey

Nothing to see here

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

enquire about this work

If this video does not start automatically, roll mouse over image and click arrow to start. enquire about this work

If this video does not start automatically, roll mouse over image and click arrow to start. enquire about this work

Nothing to see here

In his book Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder describes an art contest between fifth century artists Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Zeuxis’s painting of grapes appeared so real that, upon its unveiling, birds attempted to eat them. Next it was Parrhasius’s turn, and he asked his rival to pull aside the curtain concealing his work. When Zeuxis tried, he discovered the curtain itself was a painted trompe l’oeil. “I have deceived the birds, but Parrhasius has deceived Zeuxis,” declared the defeated artist.

Thus begins the curtain’s long and storied role in cultural history. For photographic artist Robyn Stacey, the curtain is a device designed to impart neutrality, yet nonetheless hangs heavy with resonance. This makes it the ideal subject for a pure exploration of light and colour while opening up possibilities beyond the visual. For her first exhibition with Darren Knight Gallery, Nothing to see here, Stacey has created three series of work with the curtain as their nexus.

As is alluded to in Pliny’s tale, the curtain was used in the past to cover paintings, not only for dramatic unveilings, but also for protection from the elements. Once opened, it would create a proscenium arch around its painted charge. This miniature scene is writ large in the theatrical arts, where the curtain is drawn back prior to the commencement of a performance or film.

Stacey’s suite of black-and-white photographs featuring portraits considers the cinematic aspect of this lineage. Created by projecting Super8 film onto a custom-made curtain, the resulting images explore the gaze between viewer and subject, and the luminescent attraction of early screen stars. Some of these characters are taken from B-grade 20th century European cinema, their relative anonymity enhanced through the effect of the projection. Moving close to these nearly human-scaled photographs one sees only light and shade, while stepping back from them reveals their ghostly subjects. These actors float, neither behind nor in front of the curtain, which is cast in a role Stacey has termed “a membrane between reality and allegory.” In The man who would be king, actor Terence Stamp (known in the 1960s as the world’s best-looking man) is depicted in a still from a 1980s film. His face looms through the curtain, downcast eyes ringed with shadow and dark facial hair conjuring any number of mysterious characterisations.

For artists throughout history, drapery has proven a handy device in the construction of still life composition, while the rendering of vast swathes of textile in paint or stone has provided ample opportunity for near-abstract aesthetic exploration. In the suite of coloured works Stacey has made for Nothing to see here, the curtain becomes the background and foreground, subject and object. Stacey constructed these images by projecting an image of a curtain from a scene in the 1941 Orson Welles film Citizen Kane onto the curtain in her studio. Coloured gels placed over the camera lens allow for pure exploration of colour as well as light and shade.

The colours in this suite of works were chosen for their photographic connections, ancient and modern respectively. The colours red, green and blue form the basis of colour photographic film, while gold and purple have alchemical and philosophical evocations. Unlike the suite of black-and-white images, these works have no human subjects, they are neither portrait nor landscape. However by laying bare the object of concealment, Stacey is able to create richly detailed studies of colour and light. One’s eyes trace the folds of the fabric, the tonal differences seeming also to describe changes in temperature and volume.

The term ‘photography’ comes from photos, the Greek word for light, and the inextricable connection between light and time is explored in the final works in Nothing to see here, a series of lenticular prints. These works are constructed of numerous layered images which combine to produce still, yet dynamic works. As the viewer moves before the photograph, the image shifts: through a curtain which changes from golden to grey, or a face hovering in and out of the drapery. Here, Stacey has captured a temporal, as well as physical, fluidity.

The act of ‘drawing a curtain’ can be one of either revelation or concealment. The complete etymology of the word ‘photography’ is ‘drawing with light’, and in this case the curtain acts as an extension of this notion of light as a tool, illuminating the truth and masking it. There is a familiarity and intimacy to this soft apparatus, yet a sense of grandness and authority too. Throughout Nothing to see here, the curtain is identifiable as such, its seams and hems visible at the top and bottom of the composition. The space beneath the curtain and floor “lets interpretation in” as Stacey has put it, serving as a reminder of the possibilities of this theatrically suspenseful yet poker-faced device.

Chloé Wolifson

September 2019