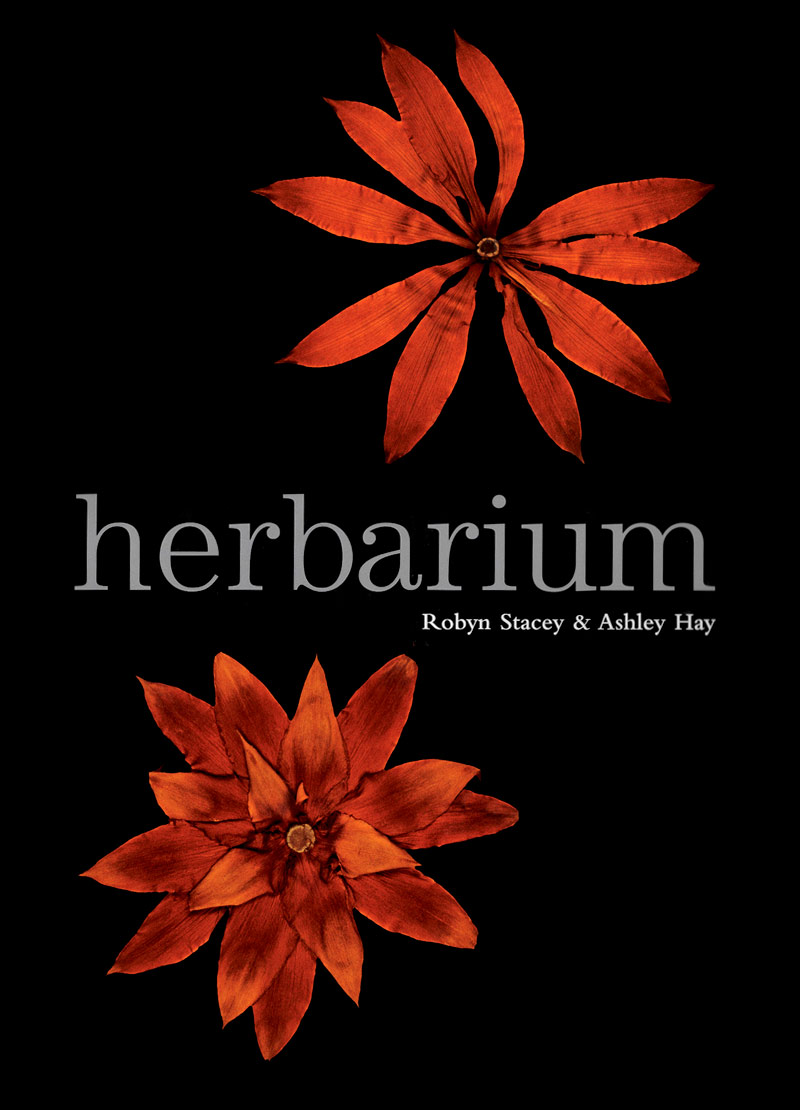

Robyn Stacey | herbarium - authors

herbarium and museum reveal two historic natural history collections that are culturally and scientifically significant nationally and internationally but are little known outside a specialist world. The herbarium collection is held at the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney, and the Macleay collection is now housed in the Chau Chak Wing museum at Sydney University.

Both books are co-authored with Ashley Hay, the current editor of Griffith Review, former literary editor of The Bulletin, and a prize-winning author who has published three novels (A Hundred Small Lessons, 2018, The Railwayman's Wife, 2014 and The Body in the Clouds, 2010) and four books of narrative non-fiction. Her work has won several awards, including the 2013 Colin Roderick Prize and the People's Choice Award in the 2014 NSW Premier's Prize.

In herbarium Ashley’s essays, explore the role of collectors and collections, nineteenth century society in Australia and the particular role of women in collecting. In museum she focuses on the Macleay family, who earnestly believed they could collect one of everything in the world and worked tirelessly developing their collections to achieve this end. She examines their significance in terms of science and society in nineteenth century Australia.

The scientific and historic notes, written by the relevant scientists and curators from each institution, present interesting historic and scientific information about each specimen or artefact showcased in the book.

There are four visual chapters in each book, focusing on the specimens, which are at the heart of the collection. This approach gives the reader a number of ways of accessing the collection- via the essays and stories around the specimens, the scientific or historic information relating to each plant or object, and the images of the specimens or artefacts themselves.

I spent years researching and photographing the collections – herbarium spanned three years and museum was a similar period of time. This long lead-time gave me the opportunity to think about the collections and how to present the very varied types of specimens, objects, and artefacts. Although I tried to photograph as much collection material that I possibly could, at the point of publication, there are only one hundred image pages in the book. While the final image selection is my interpretation of the collection it also reflects the scientific and curatorial input of the institutions and the focus of the essays.